| ||||

| "I plead before God.." -Yoram Raanan |

It was a

few years back, and my wife and I were just settling into our new home after an

exhausting move from New York to Los Angeles. At about 2 a.m., we awoke to what

sounded like cannon balls crashing outside our window. We headed for the door,

and, under the yellow halo of streetlamps, found a dozen neighbors staring in

shock at four wrecked cars.

In the

middle of the road, a young man, maybe 19 or 20, wandered about like a lost

child at an amusement park. Dazed, he mumbled like an incantation: “My life is

over … It wasn’t even my car … My life’s over ....”

Someone

asked, “How did you manage to hit three parked cars?”

“Texting,”

he replied.

By 3 a.m.,

the police had arrived. Their explanation was different: DUI.

Handcuffed

and seated in the back of the squad car, the young man’s face was ashen. He

looked like he regretted the day he was born. I fell asleep wondering how long

would it take before this young man would smile again? Would he see the sunrise

from a county jail cell?

It made me

think of this week’s Torah portion, Vaetchanan, which begins with Moshe pleading

to enter the Promised Land despite a terrible mistake he had made earlier. “I

beseeched God … Please, let me go over, that I may see the good land that is

beyond the Jordan” (Deuteronomy 3:23-25).

According

to the Midrash, Moshe’s despair was as boundless as the sea: “Moshe donned

sackcloth and put ashes on his head. He said to God, ‘Let me at least go as a

beast of the field.’ ‘No.’ ‘Let me go as bird,’ ‘No.’ ‘What of my bones?’ ‘No’ ”

(Yalkut Shimoni).

Moshe was

punished for unleashing his temper upon the children of Israel, for striking

the rock in anger, and what was done and could not be undone. Despite his

regret, no matter his remorse, Moshe would never enter the Promised Land. As it

says in the Torah, “God was wrathful … and would not

listen” (Deuteronomy 3:26).

But what

does Moshe do next? How does he deal with his mistake and the greatest disappointment

of his life? After Moshe concludes his initial speech at the beginning of the parsha and just before the repetition of

the Ten Commandments, the Torah records something that seems rather

out-of-place.

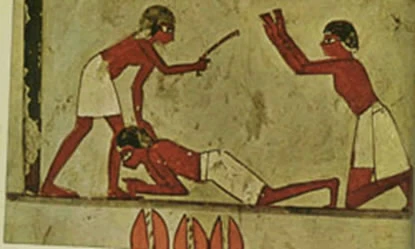

“It was

then that Moshe designated three cities of refuge East of the Jordan, from

where the sun rises” (Deuteronomy 4:41). Cities of refuge — arei miklat

— were designated for those who murdered without intent. The example the

Torah gives is when the axe head flies off the handle, striking a passerby.

Today, it could be the driver who hits a pedestrian while texting or because he

or she was flush from drink.

The

question is asked: Why does Moshe himself designate these three cities,

since the commandment to set aside cities of refuge was not required until

Canaan had been conquered? The responsibility seems like it should fall on the

shoulders of Joshua, not Moshe! Furthermore, why do we need to be reminded that

the East Bank of the Jordan is where the sun rises? The sun always rises in the

east.

The Talmud,

Tractate Makkot (10a) gives the following answer: Said R. Simlai: “What is the

meaning of the verse, ‘Then Moses separated three cities beyond the Jordan,

toward the sun’s rising?’ Said

the Holy One Blessed be He to Moshe: ‘You have made the sun rise for murderers.’

”

We have to appreciate

the symbolism of the Talmud. Here we have Moshe facing west — towards Jerusalem,

Hebron, Beersheba … and the sunset, Moshe is approaching the end of his life, and

while he may not enter the homeland of the Jewish people, he decides to

designate cities of refuge in the east, in the place where the sun also rises,

for those who must flee their homeland, for those who seek a new day.

In other words, Moshe takes

his despair and he channels it. “I beseeched God”— Here I am at the doorstep of the Promised

Land and I am denied entry for the things that I have done. But I am not going

to collapse from regret; rather, I am going to do something for those who

suffer from the worst kind of regret imaginable: Those who have taken a life. I

am going to give them another chance.

Moshe deigns to make the sun

rise even for the murderer.

This past week

we marked the ninth of Av, when Jews around the globe recalled all the mistakes

and tragedies that have befallen us. And there have been many. Perhaps the

message of Moshe Rabbenu is no matter how terrible the night, there is always a

city of refuge, a city of hope, off in the east.

After Tisha

b’Av, there comes a morning. Even after a

terrible car crash, there is a new sun.